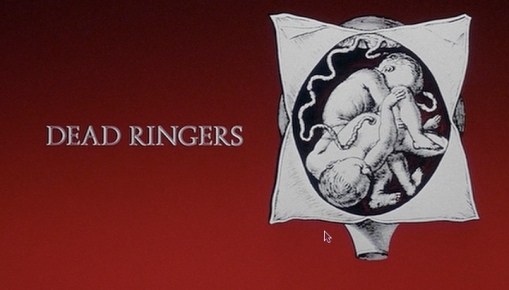

Dead Ringers

With Dead Ringers (1988) Cronenberg shows the consequences of an attempt to get rid of the space between the me and the not me. The illusory absence of difference between Mantle twins Beverly and Elliot is their own creation. They identify with one another so much that they think they are one split soul living one life in two different bodies. When they are discussing the deteriorating condition of Beverly, Claire says to Elliot that he shouldn’t identify with Beverly, distance himself from him, and live his own life separate from Beverly. In response to Claire’s suggestion Elliot says, “But the drugs he takes are running in my veins.” Beverly and Elliot are twice split. They are not only split from their mother by birth, but also from one another. They are divided within and against themselves. Let us start from the beginning to make more sense of what happens in Dead Ringers.

Right at the beginning of the film we see Beverly and Elliot, in childhood, talking about the difference between the copulation of fish and humans. One of them suggests that fish are able to reproduce without having sex, and that if humans were living under the water they wouldn’t need to have sex to copulate. They would simply internalise the water through which they would copulate. At the prospect of copulation without touching, the other twin responds by saying, “I like the idea.” The next scene shows Beverly and Elliot approaching a girl and asking her if she wanted to have sex with them in a bathtub as an experiment. They are aggressively rejected and accused of talking dirty.

Right at the beginning of the film we see Beverly and Elliot, in childhood, talking about the difference between the copulation of fish and humans. One of them suggests that fish are able to reproduce without having sex, and that if humans were living under the water they wouldn’t need to have sex to copulate. They would simply internalise the water through which they would copulate. At the prospect of copulation without touching, the other twin responds by saying, “I like the idea.” The next scene shows Beverly and Elliot approaching a girl and asking her if she wanted to have sex with them in a bathtub as an experiment. They are aggressively rejected and accused of talking dirty.

From the very beginning Beverly and Elliot see science as a means to attain sex objects and sex objects as means to carry out their scientific projects. A further hint at their tendency to see the female body as something to be experimented upon is given in the following scene where they are seen operating on a plastic doll pinned down on the table. This is their play. For them the object of desire is at the same time the object of science, and science is a form of play. Their diagnosis concerning the patient is intra ovular surgery.

From the year 1954 we shift to the year 1967. Beverly and Elliot are in the faculty of medicine in Cambridge, Massachusetts. We see them applying their surgical instrument, their own invention, on a cadaver in the autopsy room. In stark contrast to the professor’s negative attitude towards their radical new instrument, the next scene shows Elliot receiving a gold plate model of their instrument as a prize for their contribution to gynaecology. At home Beverly is working on their future contributions to the field.

The differences between Beverly and Elliot become more obvious with the entry of Claire to their life. Beverly comes to understand that he is different from his brother through his different way of being in relation to Claire. While Elliot sees Claire as merely an object of play (sex and science), rather than as another person, Beverly is more affectionate and wants to sincerely engage in a profound interaction with Claire. And yet Claire’s sexual identity, that is, her masochistic tendency to occupy a passive and submissive position in the relationship makes it impossible for Beverly to escape from the double bind situation he finds himself in. The whole film is a narrative of how one falls into a double bind situation and why it is impossible to escape from this double bind without having to die.

In Dead Ringers the Mantle twins are locked in the mirror stage. Death emerges as the only way to escape from this entrapment in an endlessly self-perpetuating process of projective identification. Their minoritarian nature, having been born identical twins, leads them to study the womb as the monster that gave birth to them. The Mantle twins’ fascination with deformed wombs, and the instruments they invent to act upon those deformations reflect their deviant relation to birth, motherhood, and sexuality.

At the culmination of the historical effort of a society to refuse to recognize that it has any function other than the utilitarian one, and in the anxiety of the individual confronting the ‘concentrational’ form of the social bond that seems to arise to crown this effort, existentialism must be judged by the explanations it gives of the subjective impasses that have indeed resulted from it; a freedom that is never more authentic than when it is within the walls of a prison; a demand for commitment, expressing the impotence of a pure consciousness to master any situation; a voyeuristic-sadistic idealization of the sexual relation; a personality that realizes itself only in suicide; a consciousness of the other than can be satisfied only by Hegelian murder.[1]

In the relationship between Beverly and Elliot, the other consciousness is at the same time the consciousness of the self. Beverly and Elliot think that they are the same and yet different from one another at the same time. An impossible situation is situated in the context of gynaecology and the psychic life of a male gynaecologist’s relation to a female patient is used to show what happens when art-sex-science become one. The “voyeuristic-sadistic idealization of sexual relation” Lacan is talking about is precisely the Mantle twins’ relation to the female body and sex. Because they see themselves as a deviation from the norm, they see their mother as the birth giver of an abnormality. Their fascination with the ill-formed female body thus gains a significance in terms of their relation to their mother and birth.

The very existence of imagination means that you can posit an existence different from the one you’re living. If you are trying to create a repressive society in which people will submit to whatever you give them, then the very fact of them being able to imagine something else—not necessarily better, just different—is a threat. So even on that very simple level, imagination is dangerous. If you accept, at least to some extent, the Freudian dictum that civilization is repression, then imagination—and an unrepressed creativity—is dangerous to civilization. But it’s a complex formula; imagination is also an innate part of civilization. If you destroy it, you might also destroy civilization.[2]

Cronenberg is a much more Freudian director than he would dare to admit.

Writing was in its origin the voice of an absent person; and the dwelling-house was a substitute for the mother’s womb, the first lodging, for which in all likelihood man still longs, and in which he was safe and felt at ease.[3]

Freud says that reality and fantasy, external and internal, the self and the world, the psychic and the material are in conflict and that this conflict is always experienced as pain. To compensate for the pain of this fragmentary existence man writes and tries to form a unity which he believes to have once been present and after which he is destined to strive. In Freud’s vision the subject is always in pursuit of an unattainable sense of wholeness, what he calls the “oceanic feeling.” And yet, Freud says, the subject can turn this negative situation into a positive one by creating works of art and literature in the way of producing at-one-ment with the world, although for Freud, this at-one-ment is impossible to attain, and if literature has any therapeutic effect at all, it is only to the extent of turning indescribable misery into ordinary unhappiness. Freud says, “the substitutive satisfactions, as offered by art, are illusions in contrast with reality, but they are none the less psychically effective, thanks to the role which phantasy has assumed in mental life.”[4]

Freud’s idea that imagination in general and writing in particular is a desperate attempt to return to the womb, to the state of being before birth, is clearly manifest in Dead Ringers. In the womb Beverly/Elliot was one and their choice of profession is a sign of their striving for that long lost oneness within themselves, with each other, and with their mother. What Freud, in Civilization and Its Discontents, calls the “oceanic feeling,” that is, the security of existence within the womb, tied to the mother with the umbilical cord, and swimming in the placental waters in foetal shape without the danger of drowning, is what the Mantle twins are striving for. According to Cronenberg they wish they were fish. Cronenberg sees barbaric regress as an inevitable consequence of progress.

This gives us our indication for therapeutic procedure – to afford opportunity for formless experience, and for creative impulses, motor and sensory, which are the stuff of playing. And on the basis of playing is built the whole of man’s experiential existence. No longer are we either introvert or extrovert. We experience life in the area of transitional phenomena, in the exciting interweave of subjectivity and objective observation, and in an area that is intermediate between the inner reality of the individual and the shared reality of the world that is external to individuals.[5]

Freud’s and Winnicott’s methods of therapy are based on the pursuit of a lacking sense of unity of self and the world. This form of therapeutic procedure forces the subject to ego formation, normalization, and submissiveness to the existing order of meaning. Freud considers the state of being in harmony with the world as the sign of health and development of the capacity to repress the drives and making sharp distinctions between the internal and external worlds, and between the conscious and the unconscious mind as a sign of progress. Although Winnicott, like Freud, assumes that there is an originary split between the internal and the external worlds, he at the same time differs from Freud in that his therapeutic process involves some kind of a journey that the therapist takes with the patient. In this kind of therapeutic relationship the therapist engages in a spontaneous interaction through playing with the rules of the game itself. In this process the role of the therapist is to render the patient capable of learning to play. In turn the therapist himself learns to relate to the patient through a kind of unconscious communication.

What we have both in the Mantle twins and Freud and Winnicott then, is a will to transcend the material world through material tools. Mantle twins’ aim is to go beyond the material world and unite with one another in a dimension where the psychic and the material, the self and the other become one. The surgical instruments Beverly invents after Claire goes away for two weeks, are parallel to his mental deterioration. As he turns against himself, so do the surgical instruments turn into weapons against the patients. The sharp and pointed instruments represent Beverly’s regressive movement towards aggressive barbarism. The Mantle Retractor is replaced by objects to dig into the body. These instruments are a result of Beverly’s attempt to externalise the illusory space created by loss of the object of love. By digging holes he thinks he will have restored himself. The instruments he creates eventually turn against him and his brother, destroying both in the process.

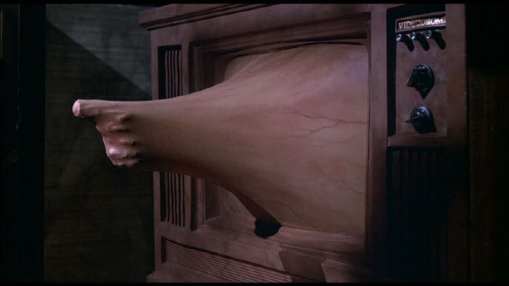

Videodrome

It is a recurrent theme of Cronenberg films that what the subject himself created turns against the subject and becomes the very cause of the subject’s death. In Videodrome (1982) for instance we see Max, the victim of a video program which is inserted into the subject’s body and possessed, the subject acts unconsciously in the service of the monstrous forces behind the screen. All Videodrome tapes do is to bring out what’s already in the subject. That is, make the subject’s unconscious fantasies appear on the surface of the screen. In other words it turns the subject into a projection-introjection mechanism. At the end of the movie we see Max’s hand turning into the gun he was holding. He is seeing himself on the screen killing himself, and in the next scene he is killing himself in front of the screen onto which he had already projected the scenario of his own death. He introjects what he himself projects, and what he projects is already an effect of what he had introjected. What we have here is a deconstruction of the relationship between the screen and the mirror. Not only the screen is a mirror, but also the mirror is a screen. The Videodrome tapes are the partial-objects which when united through the subject’s body, take over the body and manifest themselves in the actions of the subject. The subject becomes, in a way, an object of violence against itself and others.

[1] Jacques Lacan, Écrits: A Selection, trans. Alan Sheridan (London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1977), 7

[2] David Cronenberg, Croneberg on Cronenberg, ed. Chris Rodley (London; Faber and Faber, 191992), 169

[3] Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, trans. James Strachey (London: Penguin, 1985), 279

[4] Sigmund Freud, Civilisation and Its Discontents, 262

[5] Donald Winnicott, Playing and Reality, (London: Tavistock, 1971), 64

Related Articles

- David Cronenberg (cinemaroll.com)

- David Cronenberg to get a horror hero’s welcome (thestar.com)

- See Behind the Scenes Video From David Cronenberg’s ‘A Dangerous Method’; Cosmopolis Likely the Director’s Next (slashfilm.com)

- Video: David Cronenberg Talks About ‘The Dangerous Method’ at Toronto’s FanExpo (slashfilm.com)

- Five things to do today: February 3 (timeoutny.com)

- Watch Viggo Mortensen As Freud In Video From The Dangerous Method Set (cinemablend.com)